Memory Reconsolidation: Emotional Relearning in Two Steps

Step1: Recall and Re-experience Emotionally Upsetting Memory

Step 2: Apply Sound or Visual Exercise

Result: Memory’s Disturbing Emotional Component Relearned/Reduced/Removed

Emotional Relearning

We respond to a new experience using our memories of how we responded to similar experiences in our past. Our memories become response templates for how we next respond to a similar encounter.

These memories/response templates are comprised of thinking, feeling and doing components, any or all of which can be changed through relearning.

Once changed these relearned templates are reconsolidated back into memory storage as blueprints.

A name given to this process applied to relearning and reconsolidating the emotional component of a memory is the therapeutic reconsolidation process or TRP.

A powerful, self-amplifying process, TRP, focused on a central disturbing memory, alters its emotional component, associated thoughts and behaviors, leaving a new template, stripped of its negative emotionality while reinforcing adaptive thinking and acting.

More About TRP

Neuroscience discoveries over the past 2 decades have provided a new understanding of how memory is maintained and updated. Called memory reconsolidation, this understanding, when applied, results in the relearning of troubling emotions.

When several widely-used, experiential helping techniques are boiled down to their active ingredients, a common pathway for triggering change can be identified. Based on memory reconsolidation, it is called TRP.

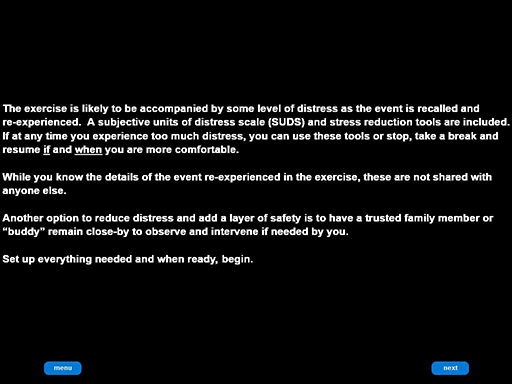

There are self-administered, self-help versions of TRP helping techniques.

A buddy system is described as a way to add support to self-administered TRP exercises.

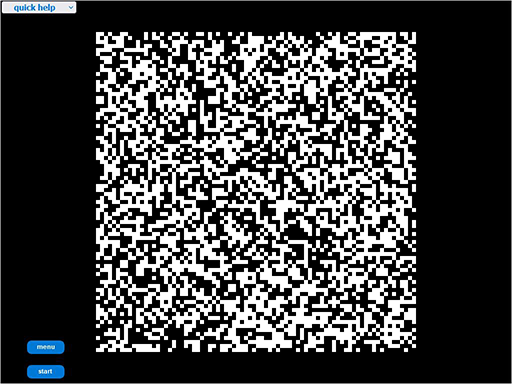

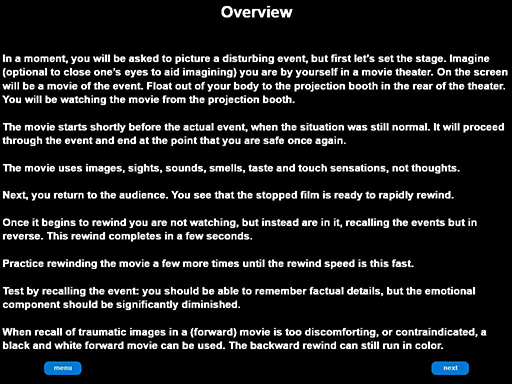

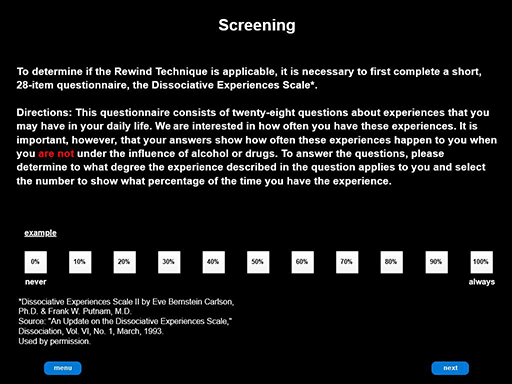

One of these, the Rewind Technique (RT), uses a visual strategy, rapidly rewinding mind’s-eye images of a disturbing event to cause the troubling emotion to be relearned. A research study using a randomized controlled trial (RCT) has provided evidence of RT’s usefulness (Astill Wright, et al., 2023).

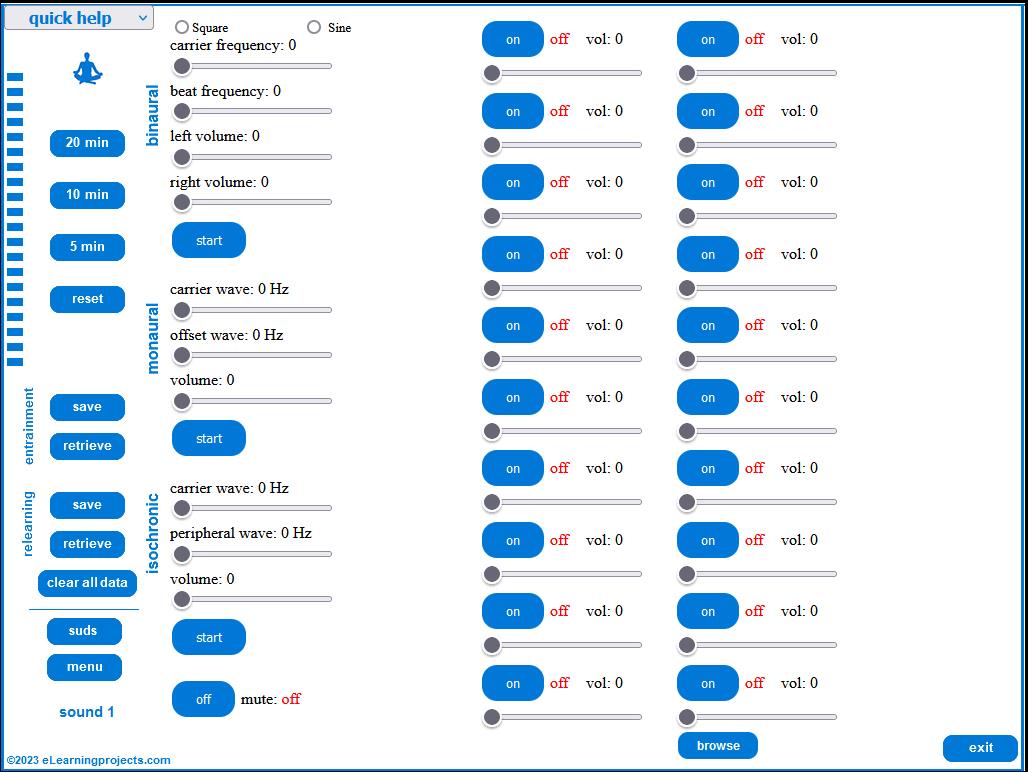

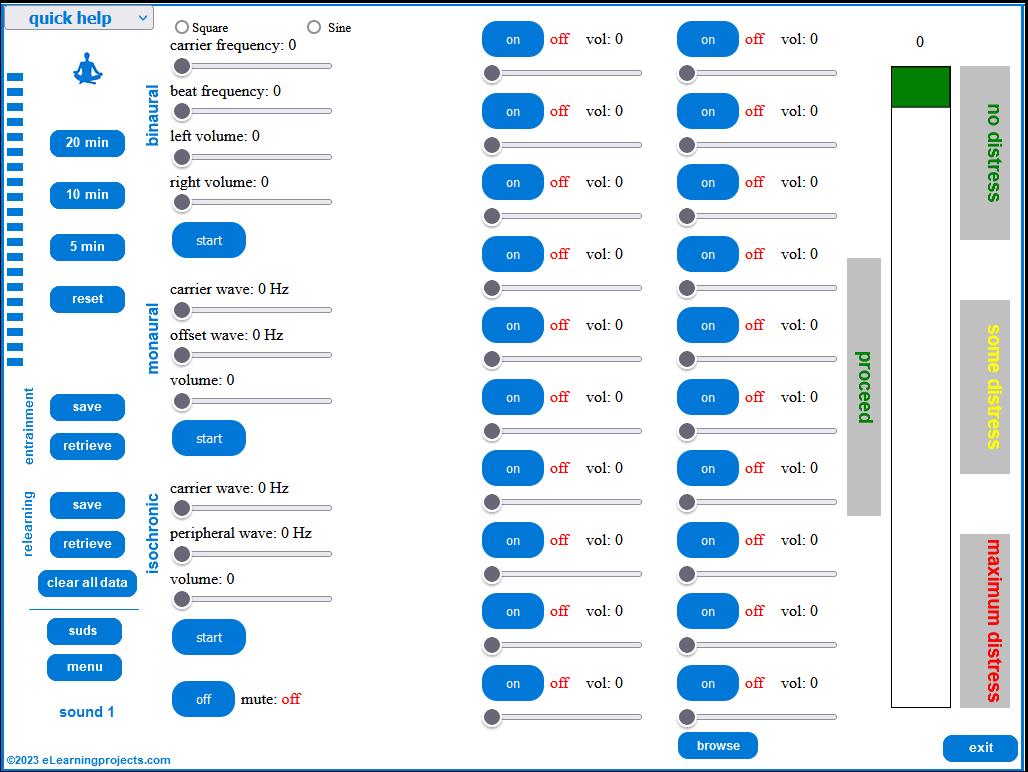

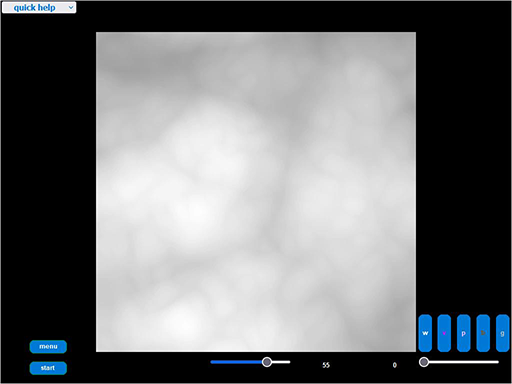

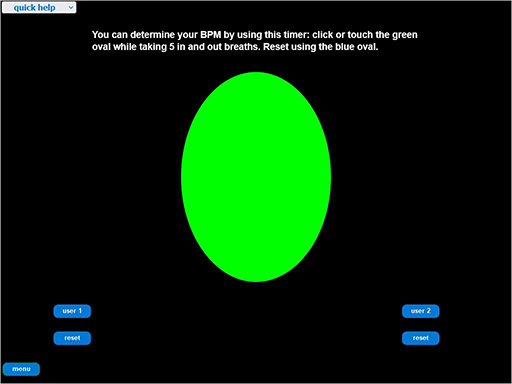

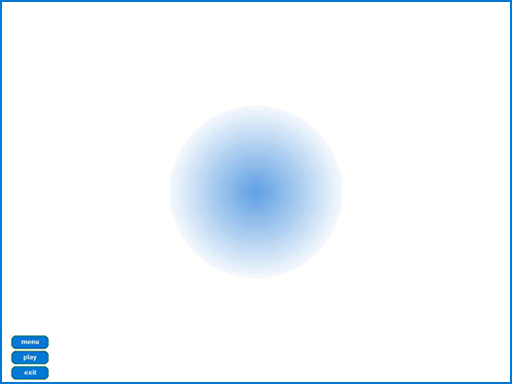

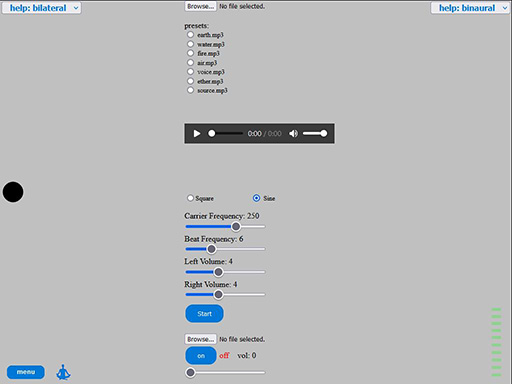

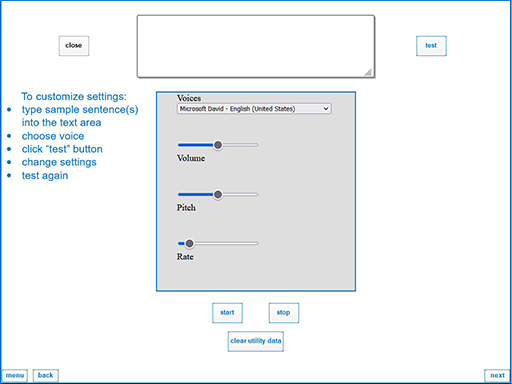

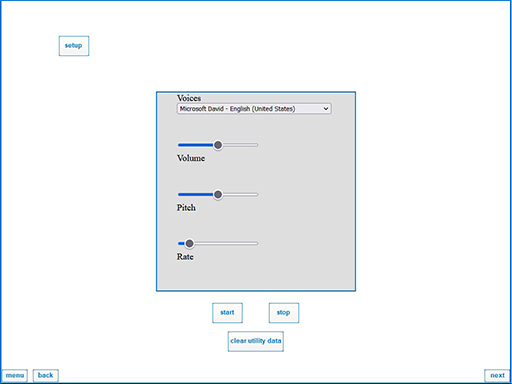

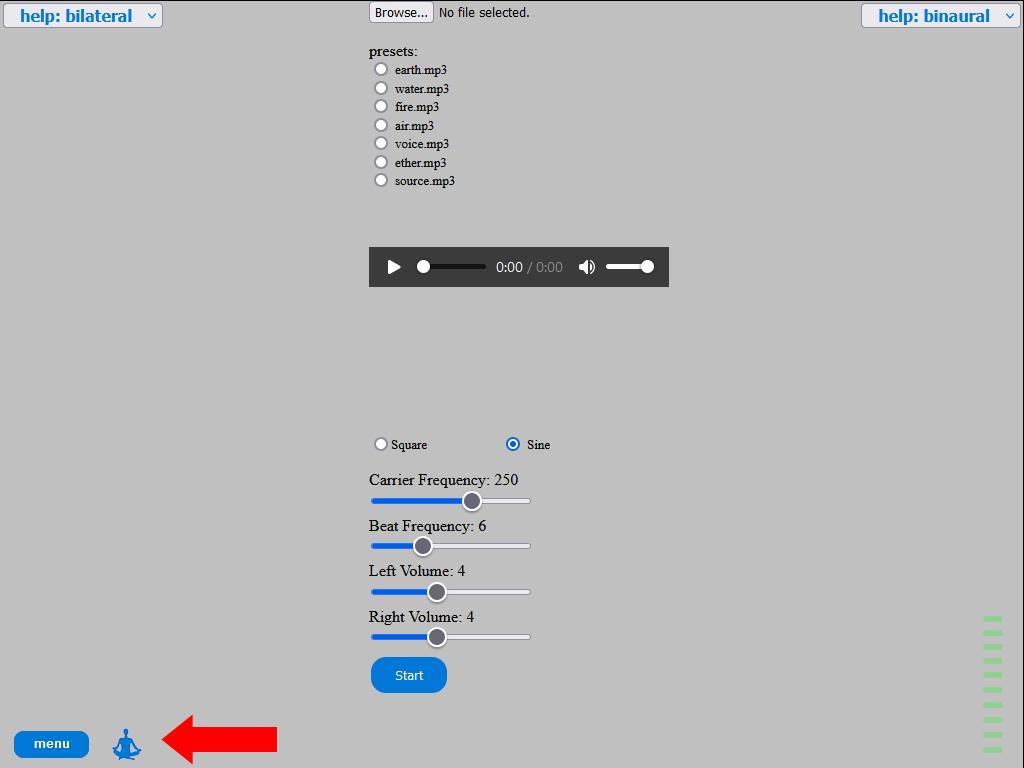

Another of these tools is based on matching/entraining a sound frequency to a mind’s-eye image of a disturbing event, then changing the frequency, triggering the relearning of the troubling emotion (screenshots below).

Both tools depend on memory reconsolidation as applied using TRP.

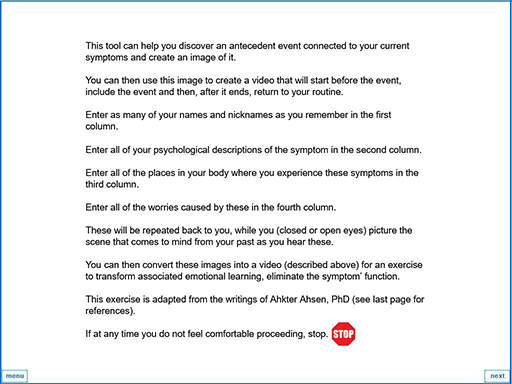

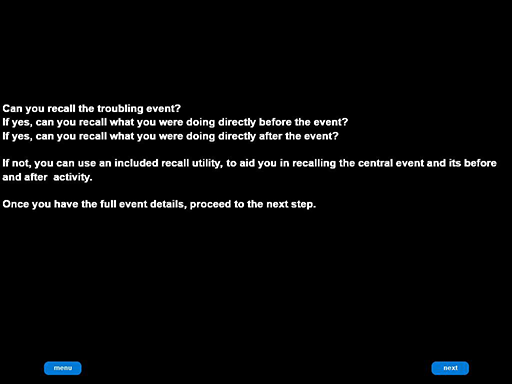

Since memory reconsolidation depends on picturing and reactivating memories of an AE, a self-administered, imagery tool is available to identify these.

Additional self-help exercises are available to support and strengthen these tools through managing stress levels.

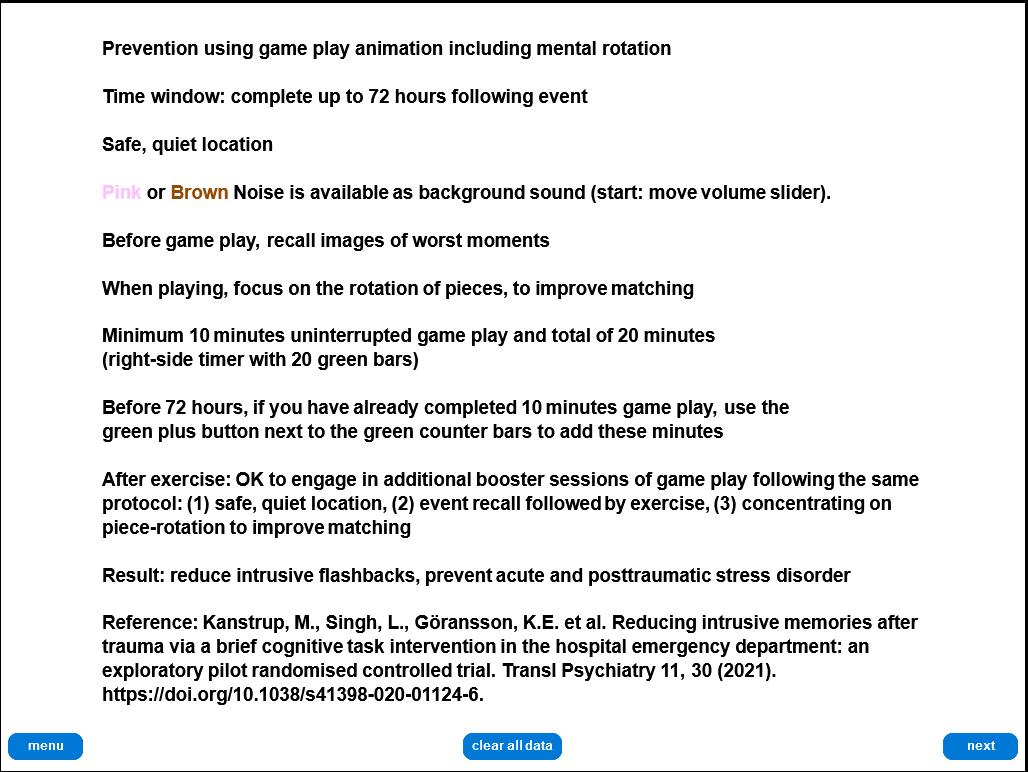

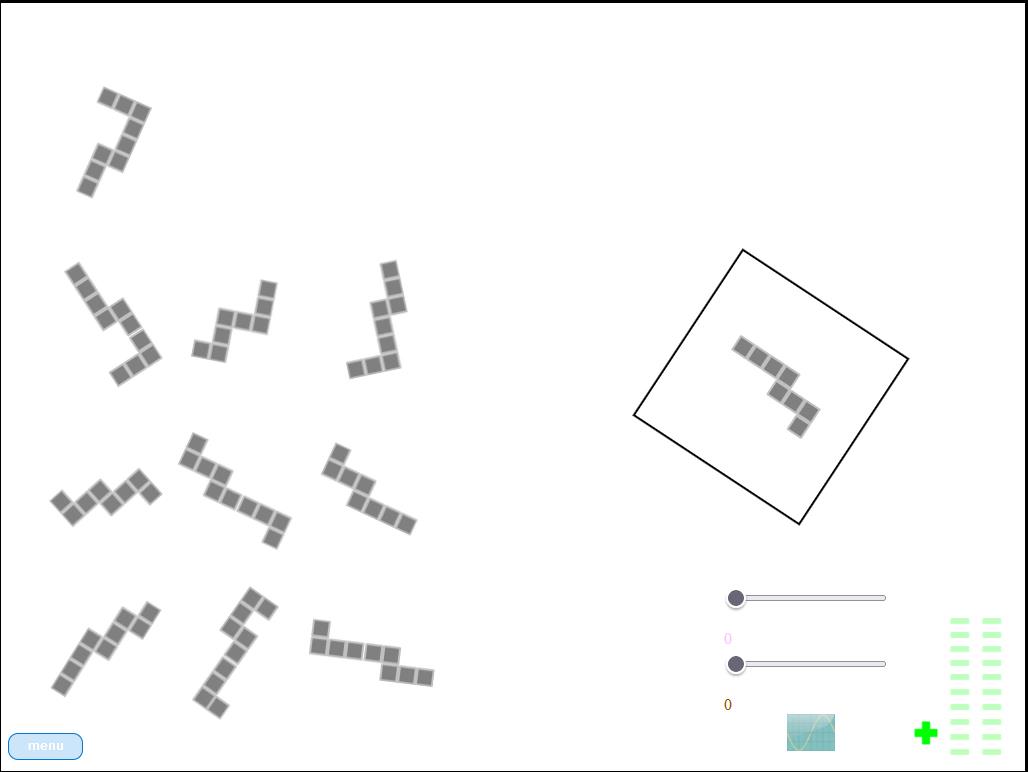

A prevention tool making use of mental rotation, to be used within 72 hours of a traumatic event, is included in the web app.

These topics are expanded below and an extensive reference list is appended documenting sources and additional readings.

Access to 5 prevention tools to be used within 72 hours of a traumatic event can be found on this site here.

Common Change Pathway

Based on neuroscience discoveries in the late 90’s and early aughts, we have a new understanding of the role that memory plays in emotional and behavioral disturbances. It describes how memory of emotion-laden events and trauma forms, consolidates, stores and, when subjected to new learning, reconsolidates. This understanding provides a blueprint for change, useful for helping a wide-range of problems. Memory reconsolidation explains how many techniques work, identifying common, active ingredients. Further, the framework allows us to integrate techniques, mix and match strategies, extend them to resolve a growing list of challenges people face. Let’s dig a little deeper into this common pathway and how it works.

Ultimately, reconsolidation is a method used by the brain to relearn, to update previous learning (Ecker et al., 2015c). Emotional learning is at the heart of how we view the world we encounter. Early on, we face experiences in our interaction with family and significant people. These consolidate, store in our long-term memory, allowing us to recall and re-use learning experiences based on these encounters. As a result, these often-unconscious, organizing frameworks, or schema, powerfully shape our subsequent perceptions and interactions.

The good news is that the brain, once considered hardwired and immutable by the end of childhood, is now seen as neuroplastic, changeable. Presented with new learning at any time in life, our brain can revise memory in line with new experiences. Memory reconsolidation is a key component of this process. When applied to maladaptive emotions and behaviors, clinical researchers have named this a “therapeutic reconsolidation process” (TRP).

If a memory serving as a foundation for an organizing framework or schema is reactivated and coupled with a similar but mismatching experience, it triggers relearning. Reactivated memory becomes labile for 4-6 hours before it reconsolidates, returns to long-term storage. During that window, TRP rewrites memory-generated schema, thereby changing associated emotions and behaviors. This understanding of TRP is based on Coherence Therapy’s (CT) comprehensive change model developed by Ecker and associates (Ecker et al, 2012; Ecker et al. 2013; Ecker, 2015a; Ecker, 2018, Ecker, 2020).

First and foremost, the key to successfully updating this (or any) targeted learning, replacing it with new learning, is to trigger reconsolidation rather than an old behaviorist standby, extinction. TRP is activated when memory of an activating event (AE) is recalled, followed by a mismatching experience similar yet altered from the original. While triggering TRP requires reactivating an AE, it does not require re-experiencing the AE’s associated emotions. However, emotional re-experiencing often occurs when an AE has caused distressing conditions like PTSD or a phobia and can be used to help identify the AE (Ecker, 2015a; Ecker, 2015b).

A mismatched experience initiated without first reactivating the original memory does not result in reconsolidation. It triggers extinction: a second memory is created that doesn’t overwrite the first, instead paralleling and competing with it. Extinction blunts associated emotions and behaviors, but they remain in the long run. Alternately, reconsolidation erases symptoms, delivering enduring outcomes.

Some symptom presentations (SX) can readily identify a key AE on which emotional learning is based, like exposure to a traumatic or phobia-inducing event. This type of memory is explicit and identified at the outset. However, other SX do not readily reveal their underlying (implicit) event. This is often the case for negative self-appraisal, long-standing maladaptive behavior. While these may seem tied to a single AE, often they are connected to additional underlying events, what the Kohut Self Psychology, other psychoanalytic theorists, label as empathic failures (Kohut. 1971, 1977, 1984; Baker & Baker, 1987). These are experienced in early relationships with parents and caregivers, while a cohesive sense of self is forming, skewing or halting healthy development. They are not immediately conscious, resulting in emotional learning more difficult to identify.

So, while the term AE may refer to a single antecedent event, it can also refer to multiple events. For example, a parent/caregiver-child relationship pattern experienced as empathic failure, which is then targeted as part of TRP.

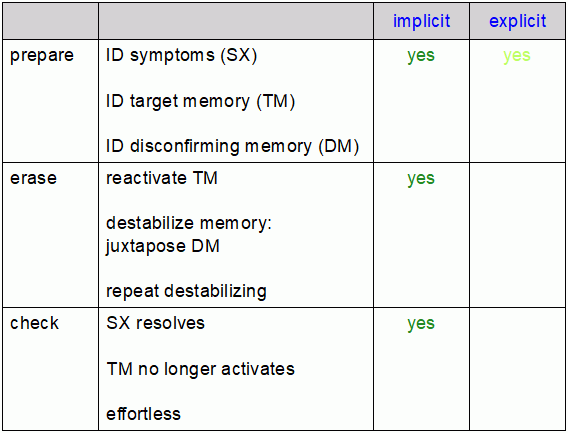

Where an AE is explicit, the change strategy can proceed quickly through CT’s preparatory steps (1) “SX identification,” (2) “retrieval of target schema” and (3) “identification of disconfirming knowledge.” Where an AE is implicit, preparatory steps require advanced uncovering strategies to bring the key memory to awareness. This takes more time, use of an additional experiential technique (for example, an imagery exercise), even facilitation by a professional helper. Once surfaced, erasure of the targeted emotional learning via reconsolidation and checking on results can follow (Ecker, 2018, p 28, Table 3).

As mentioned, CT defines TRP as the common factor and active ingredient for transformational change. TRP can be found in one form or another in many experiential therapy models (Ecker, 2018) like eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), Neuro-Linguistic Programming (NLP) and a helping strategy adapted from NLP, RT. TRP as an integrative framework (phases described in the table above) allows for mixing and matching between helping models, as long as the critical components are all present and delivered. Ecker identifies these three critical components: reactivation, mismatch and counter-learning, naming the needed process “empirically confirmed process of erasure” or ECPE (Ecker, 2018) and subsequently re-named “empirically confirmed process of annulment” or ECPA (Ecker, 2022).

According to Ecker, helping strategies, however they are mixed and matched, need to include experiencing all three of these ECPA components. At first glance, Coherence Therapy would present a different causal explanation than the dual attention hypothesis and cognitive overload/interference of the cognitive behavioral imagery researchers who focus on prevention and memory consolidation (Holmes and colleagues). The end results appear the same, but attributed to what appears to be different causes.

‘Apples to apples or apples to oranges?’ The focus of the cognitive overload/interference research is consolidation and prevention whereas the focus of the Coherence Therapy group is treatment of already consolidated schema requiring reconsolidation. Potentially an important distinction. While appearing as similar tasks, more degree than substance, each may require qualitatively different experiences to achieve results?

Also, as noted above (boldface), this difference begins to disappear when emphasis is placed on experiencing. For example, Ecker relates a clinical example using NLP where a concurrent, conscious experience of new learning with an explicit (surfaced implicit) schema (juxtaposition) sufficiently meets ‘ECPA counter-learning’ criteria (see Ecker, 2015c). So far, different causal explanations leave an as yet unanswered question. If counter-learning is experienced in a specific situation but not cognitively reinforced through an explicit statement to generalize it, while emotionally helpful in the specific experience, will the negative emotions re-appear when triggered by different experiences at different times (see Coherence-Therapy Digest, Vol 160, Issue 7)?

Recent Refinements

Over time, as memory reconsolidation has increasingly been seen as a unifying concept integrating many forms of therapy, researchers have refined and expanded these concepts (Lane, 2015; Goldman, 2020; Ecker, 2022, 2024). A recent overview by Ecker (2024) of required “core change” (transformational) “memory modification” (his latest term for ECPA) components are:

“Experience of the reactivated target memory” +

“A distinct, brief experience, during experience 1, that mismatches the target memory’s

knowings or expectations (creating the prediction error experience that destabilizes the

target memory’s neural encoding)” +

“Within 5 hours of experience 2, an experience that has subjective relevance to the

target memory and therefore reactivates the target memory, but also differs saliently

from it in the manner that is to revise the target memory accordingly, repeated a few

times for full effect (serving as new learning that revises the target memory’s neural

encoding)”

As mentioned above, therapy components that create these experiences, “purely” from one school of therapy or (carefully) mixed and matched, can produce memory modification.

So, with these provisos in mind, let’s take a look at TRP when an AE is readily identifiable (explicit), using RT and sound techniques to destabilize a traumatic memory followed by emotional relearning. A combined audio-visual technique based on bilateral auditory and visual stimulation using image (black dot) animation, coordinated with sound, shows promising results (Grifoni et al. 2023) and is included (A/V Tools: em1 slide). Eye movements prompted by the animation are saccadic which research has shown to be superior to smooth pursuit eye movements for episodic memory retrieval and quality (Propper, 2007; Propper, 2008).

RT and A/V (sound) helping techniques, whether self-administered or professionally facilitated, do not include sharing event content with anyone.

Reducing/erasing the emotional component leaves the autobiographical memory (event details) intact. Event details are able to be remembered, if later needed, for example, for legal testimony, but their emotionally disturbing component is reduced/erased.

A/V Tools

Rewind Technique

References

Adams, S. & Allan, S. (2018) Muss’ Rewind treatment for trauma: description and multi-site pilot study, Journal of Mental Health, 27:5, 468-474.

Adams, S. and Allan, S. (2019), “Human givens rewind trauma treatment: description and conceptualisation”, Mental Health Review Journal, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 98-111.

Adams, S., Allan, S., Andrews, W. et al. Four practice-based preliminary studies on Human Givens Rewind treatment for posttraumatic stress in Great Britain [version 2; peer review: 1 approved, 1 approved with reservations]. F1000Research 2022, 9:1252 (https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.25779.2).

Ahsen, A. (1973). Basic Concepts in Eidetic Psychotherapy. New York: Brandon House.

Ahsen, A. (1988). Age Projection Test: Short-Term Imagery Treatment of Hysterias Phobias and Other Themes. New York: Brandon House.

Astill Wright, L., Barawi, K., Kitchiner, N., Kitney, D., Lewis, C., Roberts, A., Roberts, N., Simon, N., Ariti, C., Nussey, I., Muss, D. & Bisson, J. (2023). Rewind for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Depression and Anxiety. 2023. 1-11. 10.1155/2023/6279649.

Astill Wright, L., Horstmann, L., Holmes, E. A., & Bisson, J. I. (2021a). Consolidation/reconsolidation therapies for the prevention and treatment of PTSD and re-experiencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Translational psychiatry, 11(1), 453. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01570-w

Astill Wright, L., Barawi, K., Simon, N., Lewis, C., Muss, D., Roberts, N. P., Kitchiner, N. J., & Bisson, J. I. (2021b). The reconsolidation using rewind study (RETURN): trial protocol. European journal of psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1844439. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2020.1844439.

Baker, H.S. & Baker, M.N. (1987). Heinz Kohut’s Self Psychology: An Overview. Am J Psychiatry 144:1, January, 1987, 1-9.

Bernstein, E.M., and Putnam, F.W. (1986). Development, reliability and validity of a dissociation scale. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, 174, 727-735.

Carlson, E.B. & Putnam, F.W. (1993). An Update on the Dissociative Experiences Scale. Dissociation, Vol. VI, No. 1, March, 1993.

Ecker, B., Ticic, R., & Hulley, L. (2012). Unlocking the emotional brain: Eliminating symptoms at their roots using memory reconsolidation. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ecker, B., Ticic, R., & Hulley, L., (2013). A Primer on memory reconsolidation and its psychotherapeutic use as a core process of profound change. The Neuropsychotherapist. 1, 82-99.

Ecker, B. (2015a). Memory reconsolidation understood and misunderstood. International Journal of Neuropsychotherapy, 3(1), 2–46.

Ecker, B., Hulley, L., & Ticic, R. (2015b). Minding the findings: Let’s not miss the message of memory reconsolidation research for psychotherapy. The Behavioral and brain sciences, 38, e7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X14000168.

Ecker, B. (2015c). Using NLP for memory reconsolidation: A glimpse of integrating the panoply of psychotherapies. The Neuropsychotherapist, 10, 50–56. doi:10.12744/tnpt(10)050-056.

Ecker, B. (2018). Clinical translation of memory reconsolidation research: Therapeutic methodology for transformational change by erasing implicit emotional learnings driving symptom production. International Journal of Neuropsychotherapy, 6(1), 1–92.

Ecker, B. & Hulley, L. (2019). Coherence Therapy: Practice manual and training guide, v190105. Oakland: Coherence Therapy Psychology Institute, LLC.

Ecker, B., Bridges, S.K. (2020). How the Science of Memory Reconsolidation Advances the Effectiveness and Unification of Psychotherapy. Clin Soc Work J (2020).

Ecker, B. & Vaz, A. (2022). Memory reconsolidation and the crisis of mechanism in psychotherapy. New Ideas in Psychology, 66 (2022), Article 100945.

Ecker, B., Ticic, R. & Hulley, L. (2024a). Unlocking the Emotional Brain, Memory Reconsolidation and the Psychotherapy of Transformational Change, Second Edition. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Ecker, B. (2024b). A proposal for the unification of psychotherapeutic action understood as memory modification processes.. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 10.1037/int0000330.

Dolan, A. T., & Sheikh, A. A. (1976). Eidetics: A visual approach to psychotherapy. Psychologia: An International Journal of Psychology in the Orient, 19(4), 200–209.

Goldman, R., & Fredrick-Keniston, A. (2020). Memory reconsolidation as a common change process: Moving toward an integrative model of psychotherapy. In R. D. Lane (Ed.), Neuroscience of enduring change: Implications for psychotherapy (pp. 328–359). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190881511.003.0013.

Gray, R. M. (2011). NLP and PTSD: The Visual-Kinesthetic Dissociation Protocol. Current

Research in NLP: Proceedings of 2010 Conference, 2(1), 33-42.

Gray, R. M., Budden-Potts, D., Schwall, R. J., & Bourke, F. F. (2020, November 19). An Open-Label, Randomized Controlled Trial of the Reconsolidation of Traumatic Memories Protocol (RTM) in Military Women. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Advance online publication. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tra0000986

Griffin, J. & Tyrrell, I. (2003). Human Givens: a new approach to emotional health and clear thinking. East Sussex, UK: Human Givens Publishing, Ltd.

Grifoni, J., Pagani, M., Persichilli, G., Bertoli, M., Bevacqua, M.G., L’Abbate, T., Flamini, I.,

Brancucci, A., Cerniglia, L., Paulon,L., et al. Auditory Personalization of EMDR Treatment to Relieve Trauma Effects: A Feasibility Study [EMDR+]. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1050. https://

doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13071050.

Hochman, J. (2007). Brief Imagery Therapy: Ahsen’s 10-Session Model. New York: Brandon House.

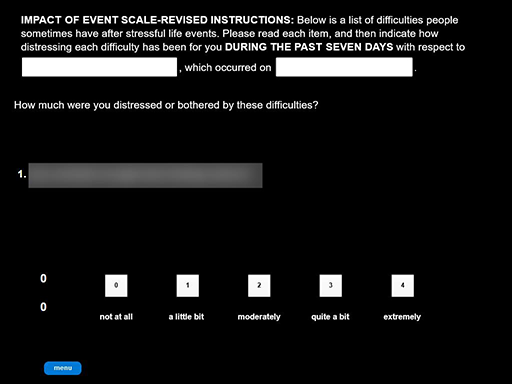

Horowitz, M, Wilner, N. & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of Event Scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979 May;41(3):209-18.

Kohut, H. (1971). The Analysis of the Self. New York: International Universities Press.

Kohut, H. (1977). The Restoration of the Self. New York: International Universities Press.

Kohut, H. (1984). How Does Analysis Cure. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Lane, R. D., Nadel, L., Greenberg, L., & Ryan, L. (2015). The integrated memory model: A new framework for understanding the mechanisms of change in psychotherapy. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 38, Article e30. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X15000011

McConnell, J. & Quinn, J.G. (2004). Complexity factors in visuo-spatial working memory. Memory, 12, 338-350.

Muss, D. C. (1991), A new technique for treating post-traumatic stress disorder. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 30: 91–92.

Muss, D. (2012). The Trauma Trap (revised edition). Kindle Desktop version. Retrieved from Amazon.com.

Muss, D. (2022). APPEAL TO ALL UKRAINIAN / POLISH THERAPISTS,PSYCHOLOGISTS,,COUNSELLORS, SOCIAL WORKERS,ETC. [Post]. Linkedin. https://www.linkedin.com/posts/dr-david-c-muss-m-d-49628014_ptsd-rewind-therapy-live-session-for-the-activity-6922507843908608000-FqEZ/?trk=public_profile_like_view&originalSubdomain=uk

Propper, R. E., Pierce, J., Geisler, M. W., Christman, S. D., & Bellorado, N. (2007). Effect of bilateral eye movements on frontal interhemispheric gamma EEG coherence: Implications for EMDR therapy. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(9), 785–788. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e318142cf73.

Propper, R. E., & Christman, S. D. (2008). Interhemispheric interaction and saccadic horizontal eye movements: Implications for episodic memory, EMDR, and PTSD. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 2(4), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1891/933-3196.2.4.269.

Quinn J. G. & McConnell, J. (1996). Irrelevant pictures in visual working memory. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 49A, 200-215.

Tylee, D.S., Gray, R., Glatt, S. J. & Bourke, F. (2017). Evaluation of the reconsolidation of traumatic memories protocol for the treatment of PTSD: a randomized, wait-list-controlled trial. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 3(1) 2017 doi:10.3138/jmvfh.4120.

Utuza, A. J., Joseph, S., & Muss, D. (2012). Treating Traumatic Memories in Rwanda With the Rewind Technique: Two-Week Follow-Up After a Single Group Session. Traumatology, 18(1), 75–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534765611412795

Weiss, D. & Marmar, C. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale -Revised. In J. Wilson & T. Keane (Eds), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York: Guildford.

Loading

Loading